Platform Ground

Audio walk + collaborative installation

by Paula Veidenbauma

Intro

Quote from the Strategic environmental impact assessment of the general plan of the North Tallinn district 2013, page 64:

“To compensate for the loss of the green network, also based on the fact that Ecobay is given the size of the development area, additional green areas must be provided. SEA recommends the compiler to build a so-called beach park, which also includes the planned beach promenade”.

Green, greener, much more green. Sparkles, more sparkles. All in the name of ambiance. The Paljassaare forest green under Ecobay glossy green. Lime Green. Imagine replacing the ocean with Yves Klein blue. Or baby blue. My baby blue. Ecobay, the invisible neighbor of Paljassaare impromptu lands, surrounds the realities of space as the unknown world of hyperreal temptation. A simulation of the idea of sustainable living that profits from never-ending speculation of possible future(s) that are born out of city development trend lines is seen as a linear process. By not embracing the biodiversity and ever-changing nature of the place, a full space beneath our feet—an unscripted universe—Ecobay uses Earth as a ground for architectural interventions. This ground—seen as empty from afar—leaves developers to manipulate with language and use it as a platform to build on rather than a space full of life itself. A platform ground.

Theoretical grounding

Based on the initial philosophical framework which defines the Ecobay project as a hyperreal experience pursued through visual abstraction, the project bases its thesis on an assumption that it provides a spectacle (Debord 1994 [1967]). The Marxist system of ’being into having’ (Marx 1977 [1885]), later developed by Guy Debord to ‘having into appearing’ (Debord 1994 [1967]: 17), has moved into a rendering abstraction, one that lives through seductive pictures and language tricks (Rosa 2016: 183). A simulation of ungrounded origins. An image-conveyed utopian realm.

The second stage of theoretical grounding, explored in the process of studio work, was based on three pillars combining historical landscape geography (Gandy 2015), anarchist planning perspectives (Sennett 1992), and materialist ecofeminist theories (Almo/Hakeman 2008) in the context of the actual realities of Paljassaare development in progress, with a focus on Ecobay territory zones B and C. Wastelands, brownfields, terrain vague: places seen as not productive enough that are being used in speculative constellations based on their appearance. In the case of Ecobay, the landscape planning is framed around aesthetics of spontaneous urban flora: one that replicates the spontaneity of nature habitats yet provides an intensification of urban landscape experience. Ecological urbanism is capitalist urbanism with design replicating forms of ecology that already exist. Often seen as places reserved for the future, wastelands are enclosed in a state of suspension.

Ungrounded simulations acquire the sense of being “off the ground”. Artificial rather than natural, abstract rather than figurative (Rajchman/Virilio 1998: 79), the to-be and here-and-there live in parallel dichotomies. When looking at the two modules of in-between lives concerning one place—Ecobay territories B and C—one can notice a certain dissonance. For Ecobay, earth is no longer seen as what anchors (Rajchman/Virilio 1998, 51), but rather as grounds: a platform to build on. A platform ground. But nature is a topos (Haraway 2008: 157), a constant movement and eternal change. Ecology is about turning. Can we learn from the modus of ecology and incorporate it into a building practice?

The third layer of research concerned the future predictions regarding Paljassaare’s west coast. With sea levels rising, the place is two meters away from sinking. Building decisions are based on trend lines impacted by the future Rail Baltica project and the Tallinn-Helsinki tunnel, but they drastically differ from the UN estimates. We can only speculate about the future. The monumentality of the Ecobay project, built as a micro-city, would not be able to adapt to the uncertainty. Many years from now, when we once again enter this abandoned garden, how will its former bricks and tiles, its concrete and steel, relate to the story of this space?

Ecobay is Paljassaare’s invisible neighbor, an unknown world around us. It lives in our imagination and perceives colors attached through renderings and simulations. The installation and audio walk invite contemplation by reflecting the place around us—from different angles and quietly—in order to become perceptive of our invisible friend, and to reveal the actualities more clearly, to question the term ‘wasteland’ itself.

Final outcome

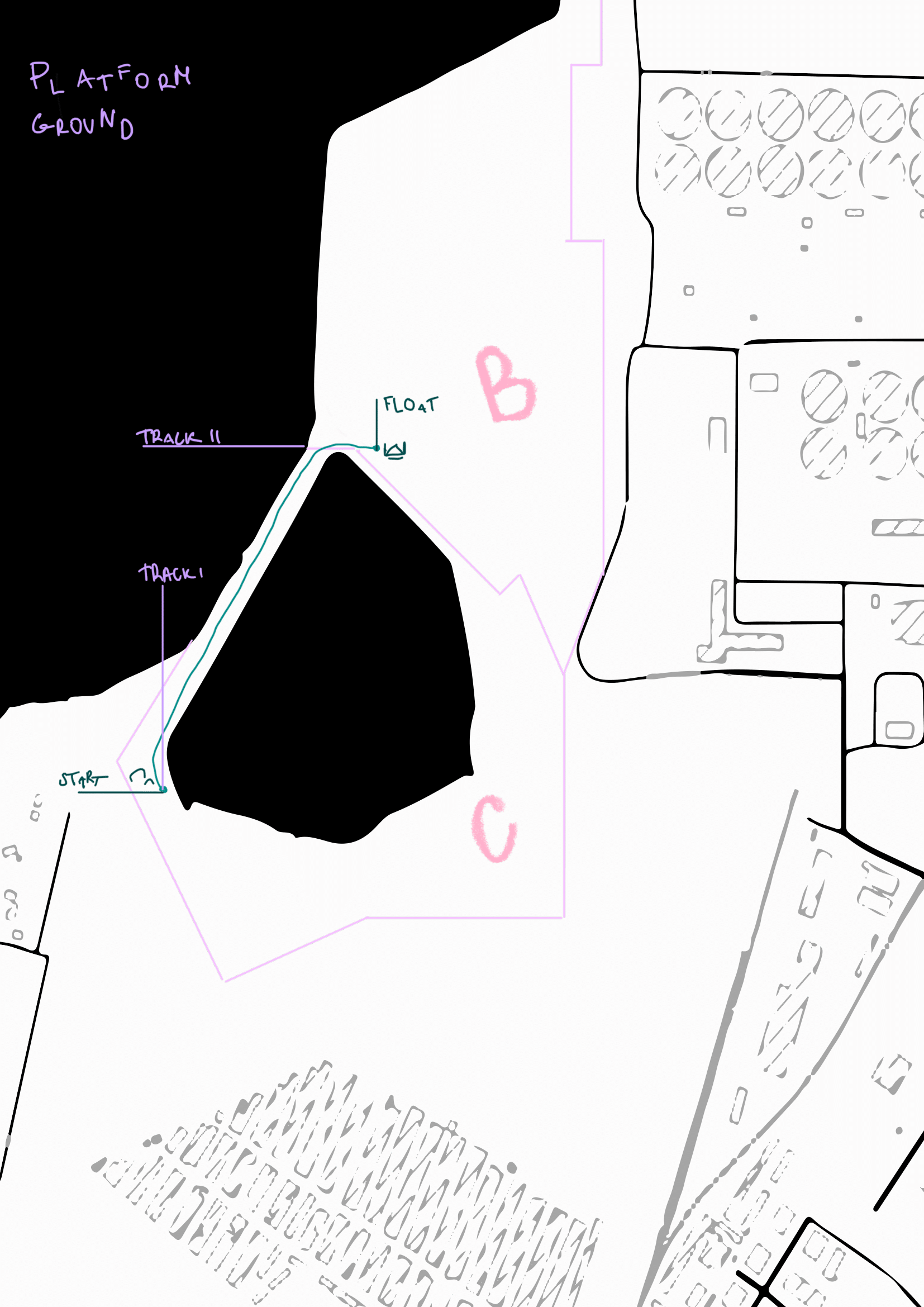

The audio walk, composed of two tracks, “Otherworldy conversations I” and “Otherworldy conversations II”, creates a foundation and a contextual framework for the collaborative soil installation on a float structure on the borderline between Ecobay territories B and C.

“Otherworldly conversations I” was developed as a background track for crossing the embankment. Consisting of both real and hyperreal content, the voice changes from human to non-human, thereby providing an alienation effect that disturbs the dramaturgy of the scene. In this context, scenery, and landscape, the reality of Ecobay territory C builds a separate entity, an independent actor of the walk. When walking over the embankment, with the wind blowing from the back, one might feel the elemental nature of the soil in oneself when trying to stand on one's feet. This is a site-specific audio walk, and the content is directly directed towards questioning the emptiness narrative of non-productivity of the wastelands used by Ecobay developers.

“Otherworldly conversations II” invites the audience to use soil as a dialogical medium for contemplation and quiet observation. The float structure is a metaphorical, loose space that uses the earth as ground. By reversing the hierarchies of putting the ecology modus on the ground, soil provides a close encounter with the smallest particles of its universe. Seen as a full space, it invites reflection on the term “wasteland” beyond its aesthetic appearance in landscape view.

The soil will disappear once not maintained, it will dissolve into its own processual nature. The collective installation is an experiment of intimate collective imaginary. When building on, what are we leaving behind?

Architecture that surrenders.

Architecture that dissolves.

Would you still call it just another pile of soil?

References

Alaimo, Stacy/Hekman, Susan. Material Feminisms. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Debord, Guy. The Society of the Spectacle. New York: Zone Books, 1994.

Gandy, Matthew. From Urban Ecology to Ecological Urbanism. Area 2015, 47: 150-154.

Haraway, Donna. “Otherworldy Conversations, Terran Topics, Local Terms,” in Material Feminism, ed. by Stacy Alamo, Susan Hekman 157–88. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Vol. II – The Process of Circulation of Capital. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1977 (first ed. 1885).

Rajchman, John/VirilIo, Paul. Constructions. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998, pp. 51-79.

Rosa, Brian. “Waste and value in urban transformation: Reflections on a post-industrial ‘wasteland’ in Manchester,” in Global Garbage: Urban Imaginaries of Waste, Excess, and Abandonment, ed. by Miriam Meissner, Christoph Lindner 181-207. Philadelphia: Routledge, 2016.

Sennett, Richard. The Uses of Disorder. New York City: W. W. Norton & Company, 1992.